![[Translate to English:] 125 Tradition und Innovation Die Formanlage in den 70er Jahren](https://www.aco-guss.com/fileadmin/standard/aco-guss/images/Home/slider-geschichte.jpg?fileVersion=1744894739)

125 years. moulded by people

Perhaps the best indication of the long foundry tradition in Kaiserslautern is certainly a casting ladle on the “Kaiserbrunnen” fountain created by Gernot Rumpf in 1987 at the eastern end of Steinstrasse.

The “Gusswerk” is one of the few larger companies in the Palatinate that can look back on more than 100 years of tradition. Founded 125 years ago, the foundry is the third oldest large company still in existence in the industrial location of Kaiserslautern.

The founding of the “Guss- und Armaturwerk A.G.” in the second phase of industrialization in 1898 was the actual “starting signal” for today's company. The long period of its existence can therefore be roughly divided into three phases: Prehistory and the foundation of a public limited company, subsequent continuation as a family business until insolvency in 1996, and the takeover and continuation of the business by the Rendsburg ACO Group since 1997.

1898

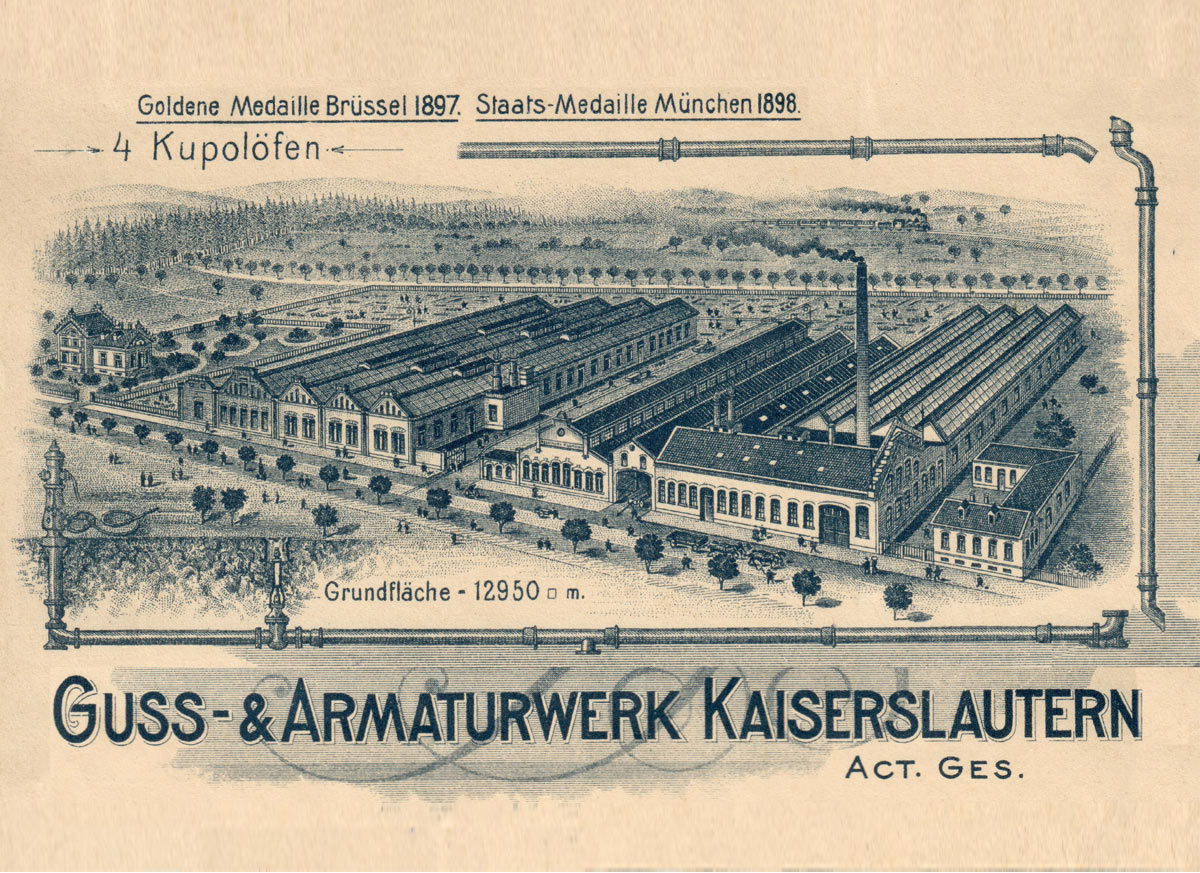

The founding of the public limited company “Guss- und Armaturwerk AG, Kaiserslautern” in 1898. The 26-year-old Karl Billand (*1872 Ludwigshafen, †1951 Kaiserslautern), who had joined the “Neue Eisen- und Metallhütte” as a commercial manager in 1898 and was now a “commercial board member” in the newly established public limited company, is regarded as the main protagonist in the founding of the new public limited company. Around 70 employees in the iron and metal foundry mainly produced water and gas fittings, hydrants, gate valves and cast-iron drainpipes.

(Image: Workforce 1897 | factory archive)

1906

The good business development up to 1903 enabled the ‘Guss- und Armaturwerk Kaiserslautern’ to purchase further land in the immediate vicinity of the factory. As early as 1904, plans to expand the company were already underway, and with the expansion of the foundry through a new building, the factory premises extended from Pirmasenserstraße in the south to Hoheneckerstraße in the north.

(Image: Letterhead 1903 | Works archive)

1908

On 2 May 1909, on the occasion of the company's tenth anniversary, the Board of Directors proudly announced that the company had ‘completely restructured’ its operations over the past few years, that workshops and other facilities had been ‘completely modernised’, that the number of employees and workers had risen from ‘135 to around 500’ and that property ownership had ‘increased from 125 to 315 acres’. Moreover, the long-awaited railway connection was now within reach, as considerable sums had been invested between 1906 and 1910 in the purchase of land and the acquisition and laying of connecting tracks to the Ludwigsbahn.

(Bild: Product catalogue 1908 | Werksarchiv)

1912

The plant continued to expand in the following years. The foundry, which in 1910 purchased and processed 3,250 tonnes of coke and 13,000 tonnes of pig iron annually from the Saar, Lorraine, Luxembourg and the Ruhr region, was expanded with a larger extension and a pattern workshop with associated warehouse was put into operation. This was followed in 1911 by a new storage area and a large boiler and machine house. Another major construction project in 1912 was the establishment of a sandblasting fettling shop.

766 workers, who had ‘4 cupola furnaces and 3 melting furnaces’ at their disposal, mainly manufactured gas, water and steam valves, hydrants, valve wells and pipe valves, as well as Scottish and German drainpipes and water pipe fittings in the pipe foundry department before the start of the war.

(Image: Factory view ca. 1912/13 | Factory archive)

1915

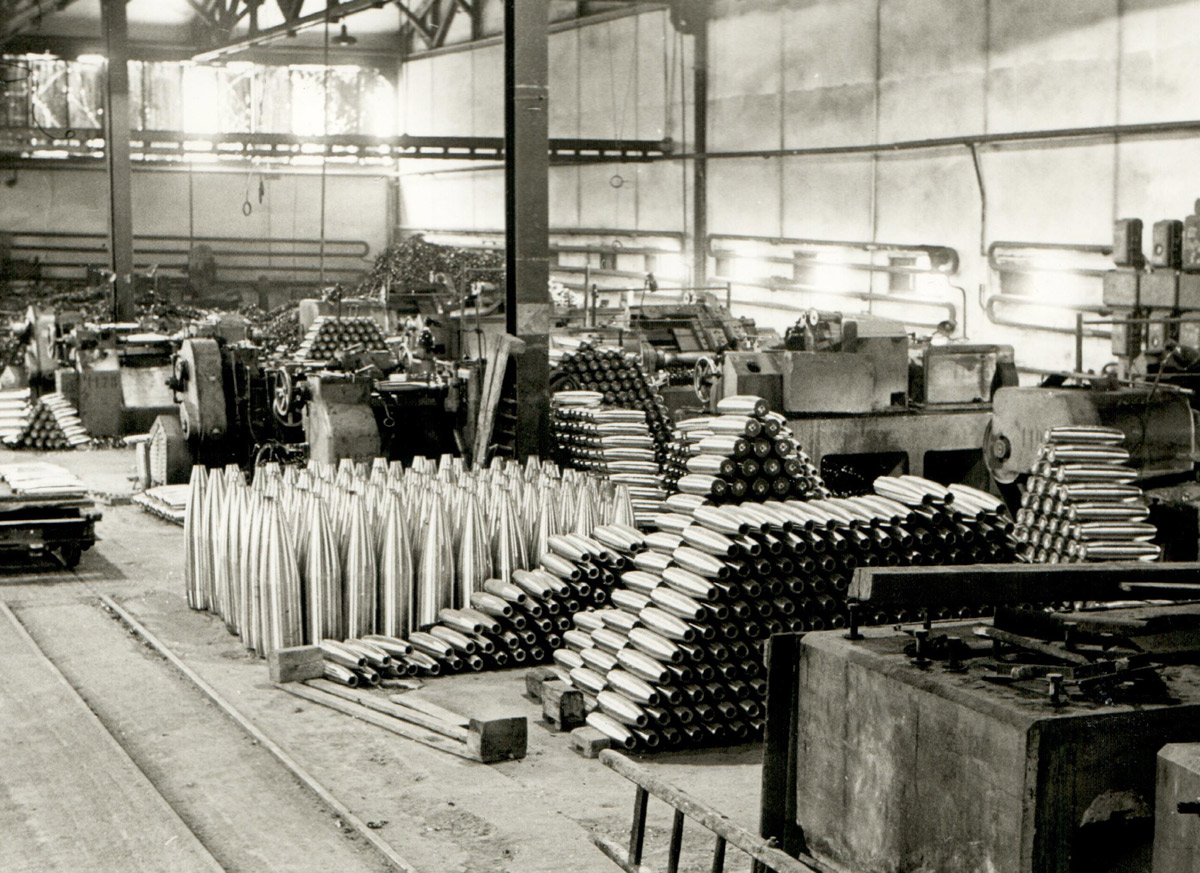

The outbreak of the First World War initially hit the factory extremely hard. Rail transport in the Palatinate was suspended for several weeks, so that business operations came to an almost complete standstill due to the lack of all primary products. Not only the markets in Western and Eastern Europe, but also overseas could only be served to a very limited extent or not at all due to the war.

In addition, more than half of the workers were called up for military service and almost all of the administrative staff. As a result, ongoing production suffered. This was changed by the increasing number of armaments orders received as the year progressed.

In order to fulfil this boom in government orders, the factory management immediately and fundamentally reorganised the factory's production, despite the continued good demand for ‘peacetime products’ up until 1916. Now, instead of pumps or pipes, all types of ammunition, especially large-calibre shell casings for grenades, were increasingly produced on a large scale in day and night shifts.

(Image: Production of shell casings by young workers in 1915 | Historisches Museum der Pfalz, photo collection).

1923

The loss of the First World War had a lasting impact on political and economic life throughout the empire.

The abrupt switch from wartime to peacetime production had already proved to be extremely problematic.The loss of armaments orders was not compatible with the previously high number of employees. Mass redundancies were the result.Instead of the 2075 workers employed in the factory at the end of 1918, only 762 people found a job in 1919.

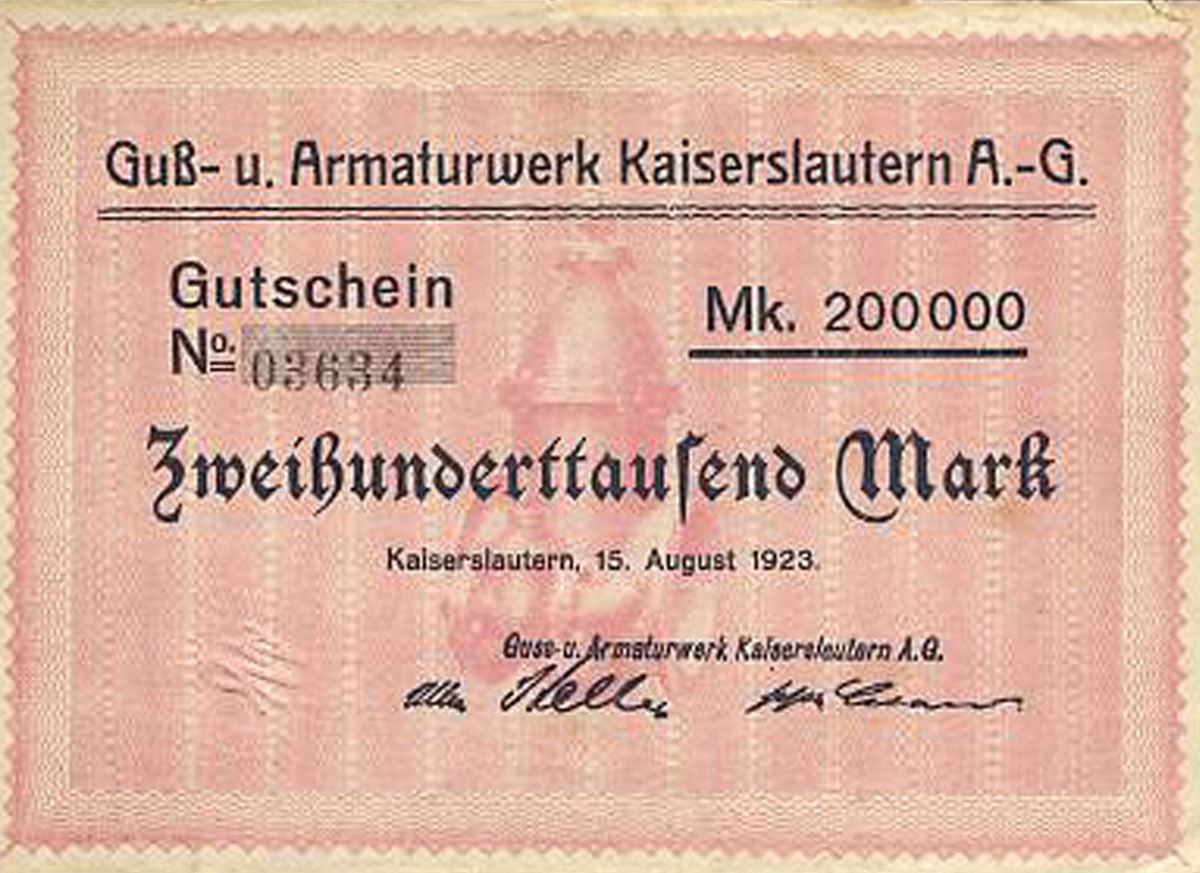

Regular business operations proved increasingly impossible in 1923. From the end of April, business operations could only be carried out with restrictions, and the factory remained closed from August 1923 to mid-January 1924.The galloping inflation affected people and the economy in equal measure. Inflation rates reached dizzying heights. Cash and savings lost all value virtually overnight.

Similar to the Kaiserslautern city administration, the Guss und Armaturwerk also issued emergency money on 15 August 1923. The company vouchers generally had a nominal value of 200,000 marks.

(Image: Emergency money of the Guss- und Armaturwerk, 15 August 1923 | Werksarchiv)

1937

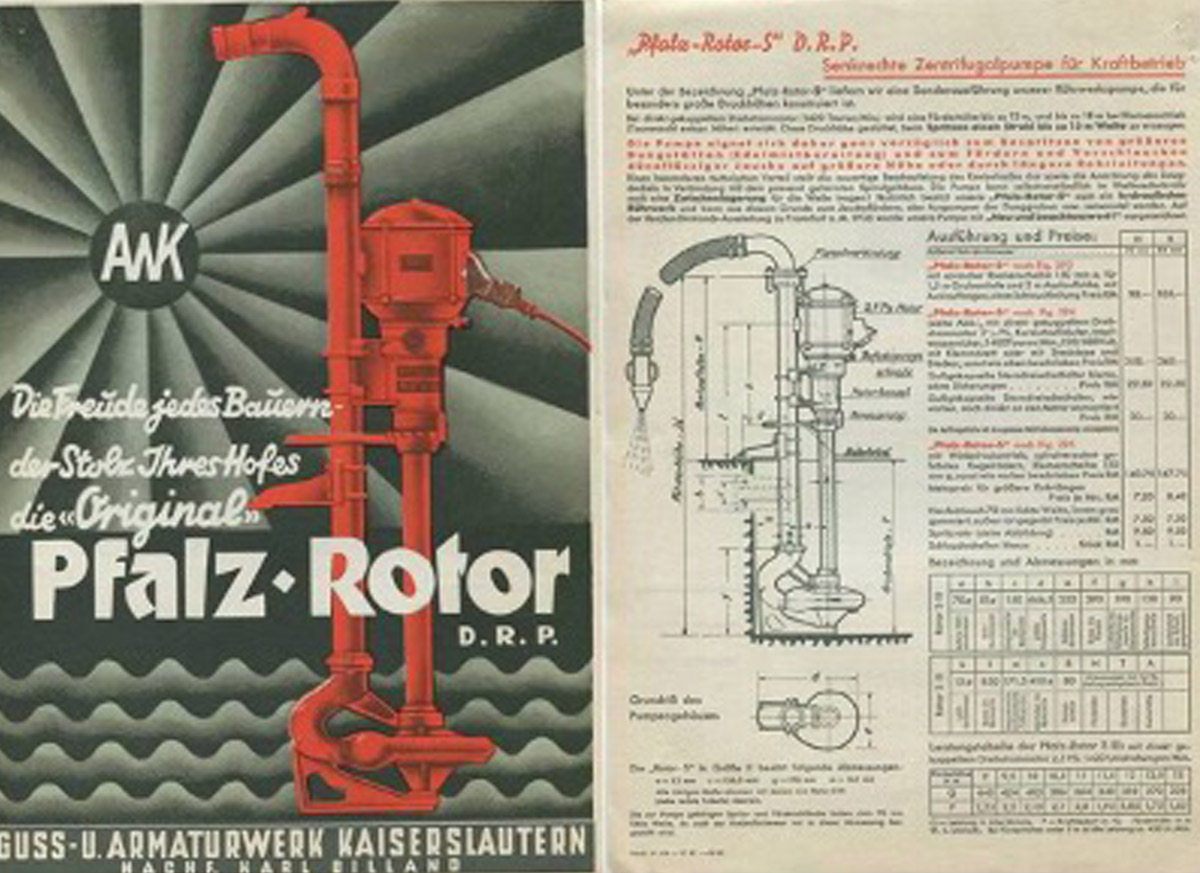

The plant benefited greatly from the political changes in the second half of the 1930s. The reincorporation of the ‘Saar region’ into the Reich in 1935 meant that coal and iron could once again be sourced over short distances, and there were now no monetary or customs barriers to the sale of plant products in the neighbouring region.

Numerous military installations, especially barracks, were built in Palatinate towns such as Kaiserslautern, Landstuhl and Pirmasens.In addition, the construction of the Westwall with its numerous bunkers was a gigantic building project along the German western border, including in the Southern Palatinate and on the Saar.Quite a few of these buildings contained products - structural steel, sewer pipes, gate valves, pumps of all kinds - from the cast iron and fittings works. As a result, the workforce grew again in 1937 to almost 100 employees and 900 workers.

In addition to the hand pumps that had been sold for a long time, the company's successful products included the ‘Pfalz Rotor’, patented in 1931

(Image: Pfalz-Rotor D.R.P. centrifugal pump - leaflet: Technical data 1937 | Works archive)

1942

During the Second World War, the casting and armature factory was forced - as in the First World War - to increasingly reduce the production of civilian goods and concentrate on the manufacture of war goods, such as 10.5 cm and 7.5 cm calibre shells as well as wheels/rollers and track parts for armoured fighting vehicles. The lucrative government orders led to an expansion of production.

At the beginning of the war, 1100 workers were employed in the casting and armouring plant. This number of employees could not be maintained, because as the war progressed, there was an increasing shortage of younger workers who were needed for military service and could not be replaced.

(Image: Production of large-calibre bullet casings in 1942 | factory archive)

1944

The city of Kaiserslautern was largely spared from Allied air raids until the end of 1943. However, this changed dramatically from the beginning of 1944. Already on. 7 January 1944, there was a major attack by British bombers. While the city area was badly affected by this and the two subsequent major raids, the ‘Guss- und Armaturwerk’ remained largely unharmed.

However, in October 1944, the factory facilities were so badly damaged by bombers of the 8th US Air Force that production could only be resumed in mid-December after extensive clean-up and repair work.

On 25 December 1944, aircraft from the 8th US Air Force again caused very severe destruction by dropping explosive and incendiary bombs. Over 70% of the factory buildings were destroyed and operations finally came to a standstill.

(Image: Destroyed factory facilities in spring 1945 | factory archive)

1948

Even before the receivership was officially lifted, the occupation authorities granted authorisation to resume production in the summer of 1948. At this time, the plant had fewer than 100 workers and employees, who had been mainly occupied with demolition, clearing and reconstruction work since the end of the war. As a result, a rebuilt factory hall was ready to receive machines as early as mid-1949.

The economic environment offered excellent prospects, demand for foundry products rose continuously and the plant was already producing 600 tonnes of steel per month in 1950/51. This ultimately made it possible to create many new jobs, so that the total number of employees rose to 900. Despite a temporary coal crisis, the plant management was able to guarantee full employment for months to come.

(Image: View of the plant after the clean-up work in 1945/46 | plant archive)

1955

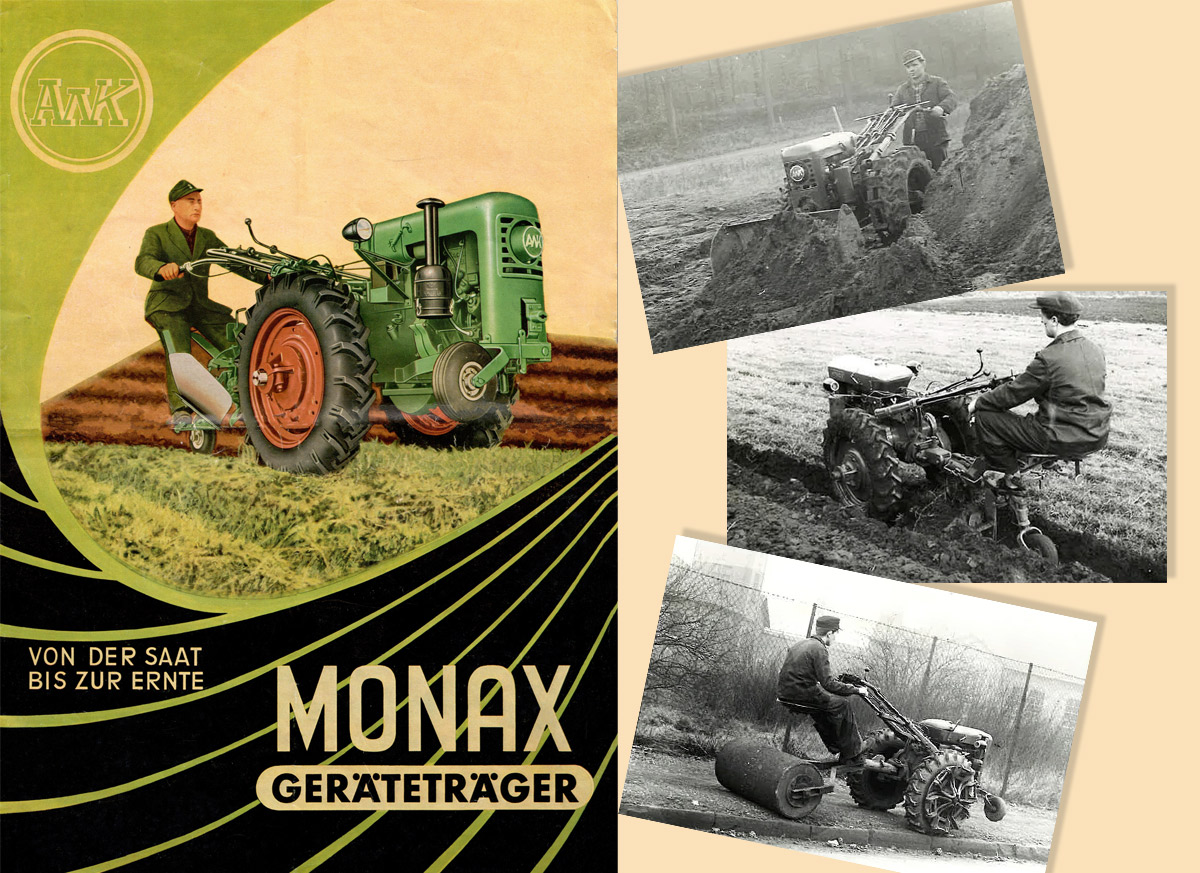

Between 1952 and 1962, the Guss- und Armaturwerk built and sold a single-axle tractor in addition to the still successful pumps and pipes. The Stamo 360L air-cooled two-stroke engine and the Sachs 500 diesel engine, both from Fichtel&Sachs, were available as drive units. However, not only the actual 107 and 107D implement carriers were manufactured, but also a wide range of accessories such as ploughs and mowers.

The Monax, which was successfully marketed throughout Europe under the slogan ‘The new helper of the modern farmer’, lost importance at the end of the 1950s with the triumph of increasingly powerful tractors.

Consequently, AWK finally discontinued production of the single-axle tractor, which had also been sold in the GDR, in 1962.

(Image: Monax advertising brochure 1955 | factory archive)

1960

The demand for the products of the ‘Guss- und Armaturwerk’ remained unbroken, so that the plant management felt compelled to expand the plant. In the years between 1955 and 1966, the rather high total sum of 27 million DM was invested every two years in the modernisation and further expansion of the plant. In 1956, a new ‘centrifugal casting foundry’ was put into operation for the production of pipes and two years later a strip processing line (with manual preparation) for the production of fittings. This was followed in 1962 by a turning plant and a roller conveyor and in 1963/64 by the modernisation of the stack casting and fettling plant.

The modernisation and new construction of the core shop and boiler house in 1965/66 only outshone the installation of a state-of-the-art dedusting system. The installation of the filter system had a longer history and was ultimately the result of the fact that since the mid-fifties, more and more housing (Karl-Pfaff-Siedlung and Bännjerrück) had been built to the north and north-west of the factory.

(Image: View of the factory from the south, around 1960, in the background the G.M. Pfaff housing estate completed in 1954 | factory archive)

1996

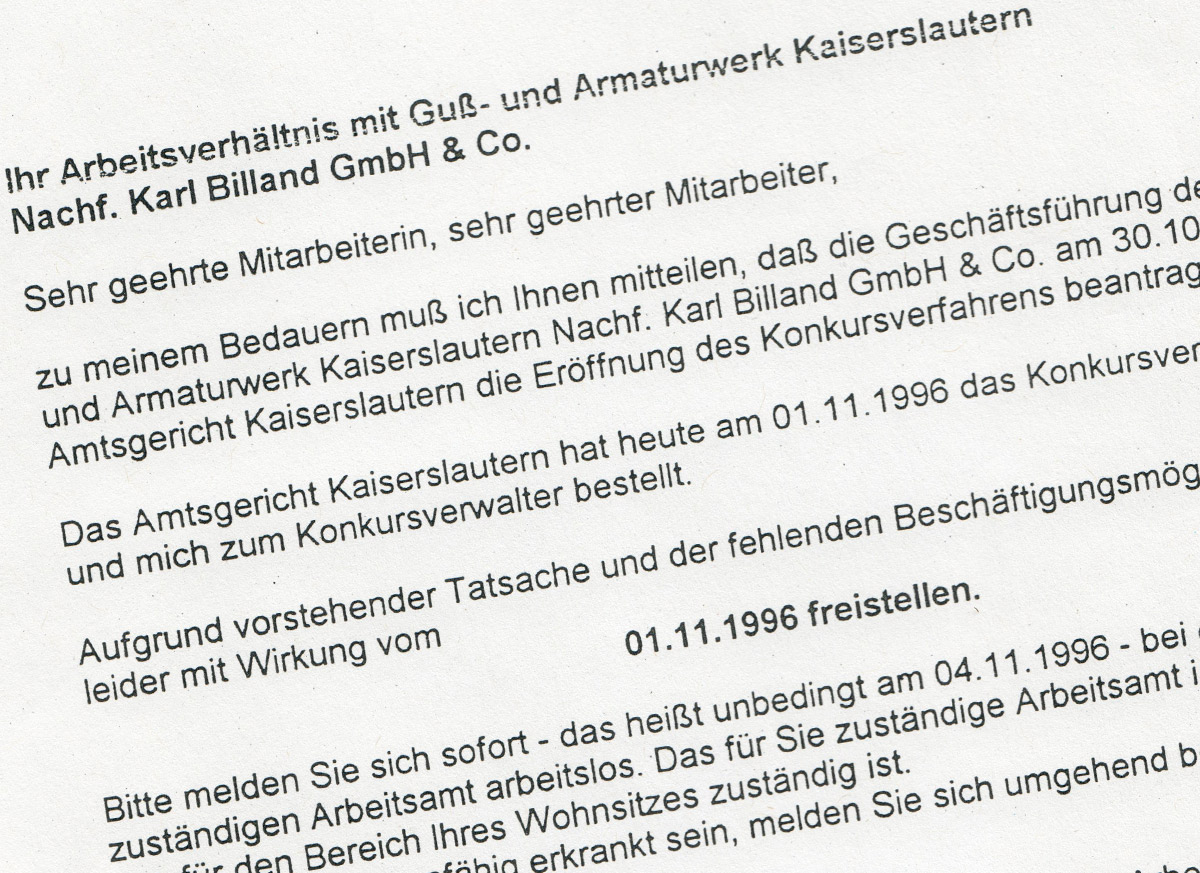

At the beginning of the 1990s, demand for the castings and fittings plant's products fell. In particular, the slump in channel casting, which had always proved to be a stable anchor during economic fluctuations, caused the plant to struggle.

The plant management responded with an extraordinary innovation - a new, fully automated production line - in order to remain competitive in Europe. In fact, the moulding line accelerated the work processes immensely and enabled very high productivity with fewer personnel.

Despite the introduction of the fully automated system, the plant continued to suffer from the unfavourable market conditions in the following year. Since the end of 1993, the ‘Guss- und Armaturwerk’ had increasingly fallen into a precarious economic situation. Ultimately, the modernisation of the technical facilities, the streamlining of the product range and the job cuts, which had been evident since 1993, were just as unsuccessful as two state guarantees and debt waivers by the two main creditors.

On 29 October 1996, the court opened bankruptcy proceedings against the assets of Guss- und Armaturwerk (AWK) GmbH & Co.

(Image: Extract from the letter of cancellation1996 | private property)

1997

In March 1997, the local press ran the headline ‘The white knight seems to have been found’ and announced that the Rendsburg company ‘ACO Severin Ahlmann GmbH’ had decided to acquire the ‘Guss- und Armaturwerk’ with retroactive effect from 18 February 1997.

The new ‘maker’ and his employees were faced with a difficult task. The protracted insolvency proceedings had left their mark on the Kaiserslautern plant.

Highly qualified employees had left the company, old customers had to be reactivated and new ones had to be acquired. The existing systems also had to be optimised and new business areas had to be developed.

As early as 1998, ‘continuous casting production’ was launched, which was to develop into a major new pillar of the plant. Extensive refurbishment and expansion measures were necessary to realise this project.

In particular, considerable preliminary work was required for the installation and commissioning of an electric induction furnace system. Behind a historic sandstone façade, a new hall was gradually built to house the melting furnace. At the same time, the factory road was completely renovated, the previously unpaved storage areas were extended and a new drainage system was installed.

Behind the historic sandstone walls, one of the most modern foundries in Europe was created

(Image: Façade of the factory hall 2015 | Factory archive)